Inspiration, and the desire to strive for a seemingly impossible goal, can come from the most unexpected of places. Could anyone imagine today a President of the United States, or the leader of any country at all for that matter, unifying a nation behind a rallying cry for the spirit of adventure? John F Kennedy did just that in a speech in Houston, Texas, in September of 1962: ’Why, some say, the Moon? Why choose this as our goal? And they may as well ask, why climb the highest mountain? Why, 35 years ago, fly the Atlantic? We choose to go to the Moon!’ We CHOOSE to go to the Moon. It can sometimes feel to us today that we are living in a world governed by the politics of division; of the building of walls to separate families, of dividing the loyalties of a nation simply in order to hold on to power, of leave or remain. What is so striking about Kennedy’s speech, more so today than it would have been in 1962, is the pure, unifying, vaulting ambition of it. And why should we go to the Moon? ‘We choose to go to the Moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard; because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one we intend to win.’ Of course, Kennedy’s motivations were not entirely pure. The constant threat of nuclear war with the Soviet Union meant that dominion over the skies was politically and psychologically important to America at the time. But the greatest achievements of humanity are rarely completely altruistic, and the kind of money that was needed to develop the Apollo program was never going to be provided by the US government without some significant, non-scientific, politically-motivated factors. There is a parallel here with Alan Turing, who was gifted the opportunity and the funds to develop an early form of digital computer, the Bombe, not through the scientific curiosity of the British government but because it would help the British to decipher Enigma-encrypted German communications. Scientific necessity doesn’t tend to motivate politicians into action so much as the threat of losing wars, or votes. Today, humanity faces perhaps the greatest challenge it has ever faced, that of protecting the Earth and everything that lives on it from irreversible harm by tackling the causes of climate change. If ever there was a time for us to unite behind a cause that is for the benefit of us all, it is now. But what are we doing? We have become consumed with petty political point-scoring, animosity and division. Wasting precious time. Professor Stephen Hawking (in his last book, Brief Answers to the Big Questions) wrote: ‘I hope that going forward, even when I am no longer here, people with power can show creativity, courage and leadership. Let them rise to the challenge of sustainable development goals, and act not out of self-interest, but out of common interest. I am very aware of the preciousness of time. Seize the moment. Act now.’ The astronaut Edgar D Mitchell (the sixth person to walk on the Moon) put it succinctly when he described how he felt when he looked at the Earth from the Moon: ’You develop an instant global consciousness, a people orientation, an intense dissatisfaction with the state of the world, and a compulsion to do something about it. From out there on the Moon, international politics look so petty. You want to grab a politician by the scruff of the neck and drag him a quarter of a million miles out and say, “Look at that, you son of a bitch.”’ Kennedy’s speech opens One Giant Leap and sets us on the journey ahead. After Kennedy’s speech (which also incorporates within it the finest poem ever written about the thrill of flying, by pilot John Gillespie Magee Jr, ‘High Flight’) we hear the echoes of our distant ancestors. For as long as we have been able to look up at the sky and wonder, we have praised the Moon and worshipped it. I also imagine the relationship between the Earth and the Moon, held forever in each other’s orbit, like lovers, but never quite able to reach out and touch. And here, William Henry Davies’s beautiful poem, ‘The Moon’, explores their romance from the point-of-view of the Earth: ‘Thy beauty haunts me heart and soul / Oh, thou fair Moon, so close and bright / Thy beauty makes me like the child / That cries aloud to own thy light’. But this highly romantic atmosphere is not all it seems. There is danger too. As Shakespeare warns us in Act 5 of Othello: ‘It is the very error of the moon / She comes more nearer earth than she was wont / And makes men mad.’ When I initially started planning and preparing the script of One Giant Leap, I didn’t want to make the piece too specifically about the astronauts. In my previous two choral works, Codebreaker and Malala, the focus had been very much on the inner-life of specific individuals - Alan Turing and Malala Yousafzai. But as I read more about Neil Armstrong and watched interviews with him and those who knew him best, I became absolutely entranced by him. And so his personal involvement with the Apollo 11 mission became an increasingly significant part of the overall piece. Armstrong was a very private man who never used two words when one would suffice. He was uncomfortable speaking in public and yet he became the most famous man on the planet virtually overnight. His was a mercurial, unknowable, almost mythical character. The greatest pilot of a generation of brave and gifted test pilots who pushed the boundaries of aviation after the Second World War that NASA drew from for their space program.

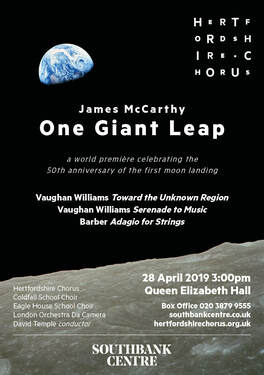

We feel the deep concern of Armstrong’s wife, Janet, as she watches the final launch preparations, and we hear Jack King’s famous countdown of the launch of Apollo 11. We also experience the unsettling strangeness of weightless flight on the journey to the Moon. Perhaps it is because Armstrong never wasted a word in his life that the power of practically everything he said whilst on the Moon was so moving and poetic. When Armstrong says ’It's very different, but it's very pretty out here’, it really means something, it is worth a thousand words by any poet. Sara Teasdale is a writer whose work I have a very close affinity to. I used four of her poems to tell the inner-story of Alan Turing in Codebreaker, and she reappears here at the end of One Giant Leap. This is both a celebration of the Apollo 11 mission and a hymn of praise to the Moon itself. ‘The Moon is a flower without a stem, The sky is luminous; Eternity was made for them, Tonight for us.’ One Giant Leap will receive its world premiere at the Queen Elizabeth Hall, London, on April 28, 2019, performed by Hertfordshire Chorus (who commissioned the work), London Orchestra da Camera, Eagle House School Choir, Coldfall School Choir and conductor David Temple. Buy tickets Recently I went to Nashville for the US premiere performances of my choral phantasmagoria Codebreaker (I’m trying not to use the word ‘oratorio’ - you should see the looks on peoples faces when you drop that word into ordinary conversation. Phantasmagoria isn’t entirely working though, is it? Needs work...) and it really had a profound impact on not just the way I see Codebreaker, but how I see all of my music, and choirs, and, well, everything really. I’ll try to unpack all of this now, but it’s very difficult to put into words. Or it is at least for me.

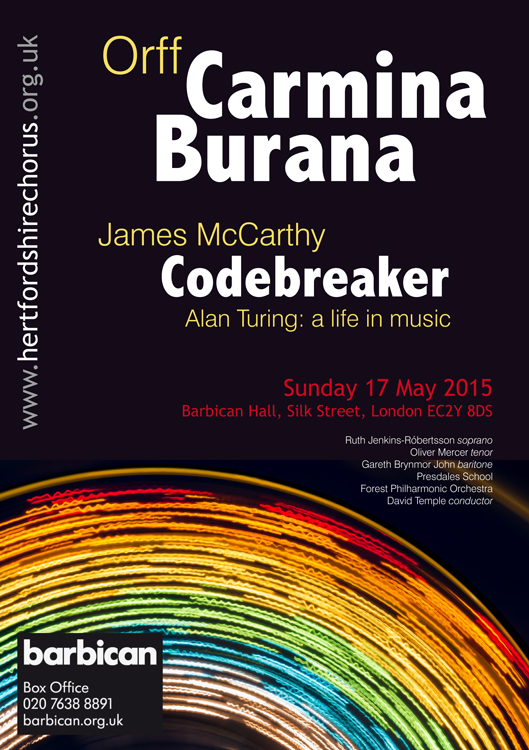

So the first thing to say is that Codebreaker tells the story of Alan Turing. Turing, of course, was many things: mathematician, runner, codebreaker, scientist, computer designer/programmer… the list goes on (as Steven Pinker said: “It would be an exaggeration to say that the British mathematician Alan Turing explained the nature of logical and mathematical reasoning, invented the digital computer, solved the mind-body problem, and saved Western civilization. But it would not be much of an exaggeration”.) And Codebreaker alights on most of these facets of Turing’s life. The piece also dwells on the fact that he was gay at a time in Britain when homosexual activity was illegal, and that when it was discovered in 1952 that he had been having an affair with another man he was subjected to chemical castration by the British government. He committed suicide in 1954. Which brings me to Nashville. The (frankly brilliant) Codebreaker performances were given by two choirs: Nashville In Harmony and One Voice Charlotte. Both choirs could broadly be described as LGBT choirs, but I don’t think that classification is quite accurate enough. They are simply groups of people where everyone is welcome and no one is judged or made to feel like an outcast. They are both, in microcosm, what the whole world should be like, but isn’t. I wrote Codebreaker about four years ago, and it seems, in a way that is quite remote from my conception and basic control over the work, to move people very deeply and in different ways. In Nashville, though, it was different. I’m lucky to have lived in and around one of the most liberal cities, London, for most of my life. And I know that, to a greater or lesser extent, homophobia is a rank societal fungus pretty much everywhere, but in Nashville you could palpably feel a sense of release, a sense of liberation, from the singers both before, during and after the performances. Nashville is a very liberal city and is completely beautiful, but Nashville is not typical of Tennessee. Now at this point, I just want to say that I absolutely hate cultural generalisations, there are amazing people everywhere and there are complete idiots everywhere (and every shade in between everywhere), but there was certainly a sense that the notion of a 'tolerant society' would not be shared as widely as it absolutely should in Tennessee. A recent Facebook post by Nashville In Harmony puts it into a little context and will, I know, be shocking to most British readers, as it should be: ‘We are sad to report that HB1111/SB1085 has just been signed into law. This law, which could prevent the state from defining same-sex spouses and same-sex parents, puts our LGBT+ families at great risk. We will continue to lift our voices in song, to resist hate directed at our community, and to continue the ongoing fight for equality.’ To find out more about this read here. And, if you want to go further, read this. So here’s why choirs matter. Choirs are the best of us. I’ve worked with choirs around the world, and you know what? At every concert, at every rehearsal, something completely electric happens. So, the choir members have had a long day at work, or doing whatever they have to do to get by, and they come into the rehearsal hall knackered and stressed, and they chat away and share a joke. Some of the singers sit looking through their music, singing quietly to themselves. Then the music director waves a hand, or claps their hands together. The room falls silent. The music director says a few words of welcome, then something like ‘we’re going to start from letter B.’ The singers turn to the right page. The room falls silent again. Then there is THE MOMENT. THE MOMENT is impossibly thrilling - a silence bursting with potential. The sound of 120 people silently adjusting their focus into precisely the same direction. The sound of 120 people inhaling together before singing as one. It’s the thought of THE MOMENT that keeps me going on days when I think ‘I’m actually never going to write another note of music again - I’m going to join the circus!’ THE MOMENT is what inspires me. It is the potential of all music summed up in a half-second’s silence. It is the embodiment of togetherness, a togetherness in which every member of the choir is equal and in which each voice can be heard. It is what the world should be, but isn't. That’s why choirs matter. What is the musical equivalent of an optical illusion? An aural illusion? Whatever it is, it is what I was aiming for when I wrote Codebreaker. The initial commissioning brief of Codebreaker was to use the forces of a large choir and symphony orchestra to tell the story of Alan Turing’s life through music. The obvious, and perhaps easiest, thing to have done would have been to have the choir act as a narrator relaying the events of Turing’s life with the orchestra illustrating those events musically. But after reading Andrew Hodges’ superb biography of Turing, I realised that this straight-on narrative approach wouldn’t allow me to explore the most fascinating aspect of the Turing story, that is, his extraordinary mind.

What kind of a mind do you have to possess in order to achieve so much in such a short space of time, that was the question that most intrigued me. So the illusion I hoped to conjure with Codebreaker was this: by asking every single one of the 150 singers in the choir ‘play’ Turing, to sing from his perspective, each singer representing a firing synapse in Turing’s brain, that this would bring his emotional and intellectual world to life so that those in the audience would be left with the distinct impression that Turing himself had been on stage, bearing his soul. Yes, it’s fanciful and presumptuous to imagine that such a thing is possible, but I’m a composer, ‘fanciful’ and ‘presumptuous’ are pretty much bullet points one and two on the job description. So did it work? Well, I’m probably the least qualified person in the world to know either way, I’m too close to the creative process, still too tangled up in the technical detail to have the appropriate distance. But I was inundated with unusually emotional responses from those who were present at the world premiere, people were clearly very deeply moved. This was perhaps best summed up by Benedict Cumberbatch (who was nominated for an Academy Award for his sensational portrayal of Turing in The Imitation Game) who sent a message to say: 'I gripped the side of my seat trying not to weep. And failed... Deeply moving to all those increasingly familiar with Turing's story and profoundly beautiful, illuminating and touching to those who are to discover him through this piece.’ And now, as the second performance of Codebreaker approaches on May 17, what I’m most looking forward to is seeing how the interpretation of the choir has been coloured over the past year. I have a feeling that this performance will be very different from the first, packing an even harder emotional punch than that remarkable premiere. Hertfordshire Chorus and their Music Director David Temple have this music in their veins, they are the people who bought Turing to life for a brief moment last year, and they are going to do it again. Whatever you do, don’t miss it. Today, Malala Yousafzai was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize alongside Kailash Satyarthi. My new work for choir and orchestra, dedicated to Malala, will premiere at the Barbican in London on October 28. Here is my introduction to 'Malala'... I don’t think I was alone in wondering, when I first heard of the assassination attempt, why the Taliban should feel so threatened by the opinions of a young girl? Why shoot Malala? An educated mind tends to be inquisitive, doubtful, questioning, innovative, logical, playful and creative. A poorly educated mind is often fanatical, certain of itself, idolatrous, extremist, paranoid, rash, reactionary and violent. An educated mind, because it is questioning and doubtful, is less susceptible to brainwashing by extremists and it cannot easily be radicalised with promises of an eternal bliss in an afterlife. This is the reason why Malala’s message – that every child, whatever their sex, deserves the right to a proper education – poses such a threat to a terrorist organisation, and why we should do all we can to lend our voices in support of hers. As Malala said at the United Nations in July last year, ‘One child, one teacher, one pen and one book can change the world. Education is the only solution. Education First.’ Bertrand Russell (with a hat-tip to WB Yeats’s poem The Second Coming) wrote, ‘The trouble with the world is that the stupid are cocksure and the intelligent are full of doubt.’ All of us know that what Malala is saying is a fundamental, self-evident truth. The instant any society in history has provided a proper education for all of its children it has begun to rise out of the dirt, becoming more prosperous and liberal, and less violent. As George Washington put it (in a line that Bina Shah quotes in the libretto), ‘education is the key to open the golden doors of freedom.’ Something else struck me as I began working on this piece. In the areas of Pakistan and Afghanistan where they held sway, the Taliban outlawed music. Why? I think it is because music appeals to both our intellect and our emotions, and encourages us to look at the world anew. In short, it educates us. An uneducated mind is untroubled by self-doubt; music makes us question everything. When David Temple first suggested the idea of a piece of music about Malala I knew I wanted to do it immediately. But I also knew that I needed to find a writer with an intimate knowledge of life in Pakistan. Bina Shah is an exceptionally perceptive and eloquent writer. When I discovered her blog I was struck as much by her clear, level-headed view of sometimes dizzying political and social events in Pakistan (where she lives) as by her inherent poetic nature. A true poet cannot hide their ability, their feel for the weight and rhythm of every word, any more than an elephant can hide its trunk. I knew that Bina was the writer this project needed. Imagine my delight when she agreed to take part. But that was just the beginning. I knew I had a great libretto to build on, but still – how do you go about setting real events as powerful and significant as these to music? All of the pieces I’ve written have been difficult. I’ve never been one of those composers who can just rattle something off. Every time I sit down to write a new piece of music I feel as if I’ve never written so much as a quaver before in my life. I ask myself: why am I doing this? This is crazy, trying to lasso sounds out of the ether, and for what? But I think that anyone who has ever created anything has experienced these thoughts, these moments of near-crippling self-doubt, and in fact they may actually be critical to the creative process. They certainly seem to be crucial to mine. The most important thing is to keep pressing on, no matter what. And when an idea does eventually start to flow, and then when that idea is performed with great artistry and commitment by a choir like Crouch End Festival Chorus… well, there is no feeling like it in the world. This piece is dedicated to my daughter, who has taught me more about life than I am able to fully comprehend. I’m still learning. We are all Malala. Watch Bina Shah introduce the Malala project below: Writing a music drama about Alan Turing was a far more complex and dizzying undertaking than I had first imagined it would be. In a way, the story of Turing’s life is a composer’s gift: an eventful and ultimately tragic existence that had vast repercussions, the reverberations of which we are still feeling today. And yet it was a life shrouded in mystery. Turing left behind surprisingly few clues regarding what he felt about, well, anything at all. He was a private man dedicated to his passion for scientific and mathematical enquiry. But he was also a national hero whose genius saved millions of lives during the Second World War and who died as a result – at least in part – of persecution from the country he was instrumental in saving from oblivion. His is the clearest claim to the title ‘inventor of the computer’, thereby allowing me to type this on a train as it wheezes its way through the Surrey countryside (a landscape, incidentally, that Turing would have known well in his pastime as a distance runner of near-Olympic standing). There can have been few people in history who achieved so much of profound consequence for humanity in so little time. Codebreaker isn’t a biography, complete with copious footnotes, or an exhaustive encyclopaedia entry. There are many aspects of Turing’s life that I would dearly have loved to include, but too broad a narrative arc, too meandering a musical journey, would have lessened the dramatic impact of the whole. From the outset, I wanted Codebreaker to be a portrait of a living, breathing human being and not the musical equivalent of a marble monument to a Great Hero. So I had to find the man behind the myth-making. And I found him in two ways. Firstly, through his mother’s biography (which, remarkably, Sara Turing wrote in spite of the fact that she had no knowledge of her son’s contribution to the war effort), and secondly, through the letters that Turing composed to the mother of Christopher Morcom. Indeed, Morcom was key to everything. Turing met Morcom at school and fell deeply in love with him. It is doubtful that Morcom was aware of Turing’s true feelings; their relationship was based on a passion for science and nature; they would map the stars together. Morcom was a precociously gifted young man and showed much more potential for further academic success than Turing did at the time. Sadly, Morcom died very suddenly of bovine tuberculosis at the age of 18. And we would probably know nothing of the deep pain and inspiration that Turing took from this tragedy were it not for the letters of condolence that he wrote to Morcom’s mother (‘I shall miss his face so, and the way he used to smile at me sideways.’) Falling in love with Morcom changed Turing’s life. It would be an over-simplification to say that Turing owed everything to that single event, but I believe that the desire to fulfil Morcom’s potential for him and the later investigations into whether machines could think flow from this pivotal moment. In Codebreaker I have focused on three key moments in Turing’s life, namely: falling in love with Morcom, the war, and his final hours. The piece begins with a prologue. The very first words (‘We shall be happy’) come from the final line of the piece, making Codebreaker circular. There follow a couple of lines that Turing scrawled on a postcard that I think demonstrate that he had a poetic soul: ‘Hyperboloids of wondrous light / Rolling for aye through space and time’. The prologue concludes with Gordon Brown’s apology on behalf of the British Government from 2009 (predating the more recent and controversial Royal Pardon). Brown’s heartfelt apology gives a neat overview of Turing’s life and delineates the narrative arc of the piece to follow. Introductions over, the chronological narrative of the piece proper begins as Sara Turing leads us into the feelings of rapture and elation that Turing would have felt falling in love for the first time, and how that is all unravelled by Morcom’s sudden and tragic death. We then leap forwards in time by a decade or so to the outbreak of the Second World War. Although the war was a deeply disturbing time for Turing, as it was for everyone, it is also true that at Bletchley Park he was respected, revered and accepted in a way which was quite exceptional in his life. The social life at Bletchley was vibrant and colourful, though the shadow of war hung over everything, so this music is shot through with the spirit of brilliant young minds working together to one end. At Bletchley, Turing was given responsibility for cracking the naval enigma codes, famously the most difficult enigma codes to decrypt at the time, and he did so by inventing a machine called the Bombe which greatly speeded up the process of decryption. It was one of the great intellectual feats of the 20th century. Every day bought a new code to crack which would unlock all of the German communications for the following 24 hours, so every morning there was feverish work to be done decrypting that day’s code, all the while everyone was aware that with every minute that passed thousands of sailors lives were at risk from U-boat attacks. At the time, war must have seemed unstoppable, the marching of jackboots irresistible. Yet at the same time Turing would have known this: that the natural world, the world of science, couldn’t care less about our wars, our conflicts. Nature will carry on as it always has long after we have all left this world in peace. We then jump forward in time to 1952, the year in which Turing was arrested for having an affair with a young man. Turing, as a known homosexual who had at one time been privilege to the highest level of security information, was, at least to the British secret services, a security risk. He was, to them, an individual who could potentially be blackmailed by Britain’s Cold War enemies. And so he was hounded, his movements tracked, his friends followed. The sadness is that none of this should come as a particular surprise to us today. Edward Snowden has revealed how the US and UK governments are currently monitoring every aspect of our online lives. And it is a startling irony that our computers, Turing’s invention, are allowing them to do this. So, in 1952, when Turing was the victim of a minor robbery he reported it to the police. During the investigation it came to light that Turing had been having an affair with a young man, then illegal, and so after a brief trial he was offered a choice of a prison sentence or chemical castration, Turing chose the latter. It is still shocking to realise how recently in British history this all happened. In the 1930s, Turing had been captivated by Disney’s groundbreaking animation Snow White and he often repeated the following line: ‘Dip the apple in the brew, let the sleeping death seep through’. In 1954, two years after his arrest and chemical castration, Turing dipped an apple in cyanide and took a bite. He was just 41 when he died. The final moments of Turing’s torment find their voice in Oscar Wilde’s ‘De Profundis' (written to Lord Alfred Douglas while Wilde was imprisoned in Reading Gaol). Having bitten the apple, Turing slips into unconsciousness. Approaching death feels very much like falling asleep, or entering a forest from which he will never be able to escape. Later, reeling from her son’s death, Sara Turing sings Robert Burns’s A Mother’s Lament for her Son. And that is where the story ends. Or, at least, that is where it should end. But I just couldn’t bring myself to leave Turing in the dark, frightening and lonely place he truly ended up. He deserved so much better. So here it is: I imagine that, in his final moments, he would have wished to be reunited with Morcom, as he had wished throughout his adult life. Perhaps the last image that flooded Turing’s consciousness was that of Christopher Morcom’s smiling face. So that is where we leave him, standing side-by-side with Morcom under the wide starlight for all eternity. ‘We shall be happy, for the dead are free.’ Watch the Codebreaker promo film below: Benedict Cumberbatch has his work cut out. When The Imitation Game hits the big screen later this year, we’ll know how he’s solved the Alan Turing riddle. That is: how do you portray a man who – by common consent – had a long list of eye-catching mannerisms (a grating, high-pitched laugh, a stammer of varying frequency and intensity, for starters) without completely misrepresenting Turing as a sort of jabbering loon, like Russell Crowe’s Turing-inspired character at the nadir of his nervous breakdown in A Beautiful Mind?

Turing led the world in so many disciplines – cryptanalysis, mathematics, computer science and programming, artificial intelligence, morphogenesis and more – it is barely conceivable that he should have achieved so much by the time of his death at the age of 41, 60 years ago. When I started researching Codebreaker, my new work for solo soprano, chorus and orchestra based on the life of Alan Turing, I was seduced by Turing’s multi-layered mind. The idea formed that maybe, rather than it being decidedly odd to ask 150 singers to ‘play’ Turing, in fact it may be the perfect solution to the riddle. Perhaps the rich complexity of Turing’s intellect would be far more appropriately brought to life by 150 people than by one. Not many of Turing’s most private thoughts and feelings have been passed down to us. So coursing through the singers’ text for Codebreaker are poems that I imagined would give voice to them. Oscar Wilde (his epistle ‘De Profundis’), Wilfred Owen, Sara Teasdale, Edward Thomas and Robert Burns are all there, but there’s also a speech by Gordon Brown (the government ‘apology’ to Turing from 2009) alongside tender memories of Turing as a child, loosely based on Sara Turing’s touching biography of her son. Despite the fact that Codebreaker is written on a grand scale (more than 200 singers and musicians will be onstage at the premiere) my aim was always to create an intimate experience, as though the listener is literally sitting across a table from Turing as he bares his soul. This poses a special challenge to the choir. I tend to conceive pieces cinematically whilst I’m wrestling with the dramatic structure, and in the case of Codebreaker I focused on two particular movie characterisations: Robert De Niro as Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver, or Daniel Day-Lewis as Daniel Plainview in There Will Be Blood. It’s fascinating to watch De Niro and Day-Lewis completely absorb their own personalities within the character they are playing, and how the camera hardly leaves their face for a moment. Their characters fill the frame. I wondered how it would be to have 150 singers lose themselves within the same character simultaneously. To the extent that during the rehearsal process they start to find new colours in their voice, perhaps wear their hair in a new way, dress differently. So that’s what I’ve tasked the Hertfordshire Chorus with: a kind of massed Method acting. Will it work? Well, the beauty (curse?) of being a ‘pencil-and-paper’ composer is that you’ll find out at exactly the same moment as I do at the Barbican premiere on 26th April… Nervous? Me? If you look at my previous blog, you'll see that Codebreaker was mentioned today in the House of Lords by Lord Sharkey. Below is the transcript from Hansard for all those who cannot pick up the BBC broadcast I linked to. Codebreaker will receive its world premiere at the Barbican in London in April next year:

There has also been a successful musical of Turing's life, and next year at the Barbican there will be the world premiere of a new choral work celebrating his life, composed by James McCarthy and commissioned by the Hertfordshire Chorus. Soon there is to be a new film of Turing's life. Benedict Cumberbatch is to play Turing and Keira Knightley is to play his girlfriend—which might seem a little odd, because of course, Turing was gay, and it was because he was gay that he was treated so appalling by the Government of the day. As I think everybody knows, he was convicted in 1952 of gross indecency and sentenced to chemical castration. He committed suicide two years later. The Government know that Turing was a hero and a very great man. They acknowledge that he was cruelly treated. They must have seen the esteem in which he is held here and around the world. There are two quotations which, for me, sum up Turing's greatness and establish him as a British hero. The first is from Professor Jack Good, who was at Bletchley Park with Turing and who died last year at the age of 91. Professor Good said that, “it was a good thing the authorities hadn’t known Turing was a homosexual during the war, because if they had, they would have fired him .... and we would have lost”. The second quote is from the very distinguished Harvard professor Steve Pinker in his book The Better Angels of Our Nature. Professor Pinker says: “It would be an exaggeration to say that the British mathematician Alan Turing explained the nature of logical and mathematical reasoning, invented the digital computer, solved the mind-body problem and saved Western Civilization. But it would not be much of an exaggeration”. It is not too late for the Government to pardon Alan Turing. It is not too late for the Government to grant a disregard for all those gay men convicted under the dreadful Labouchère amendment and similar Acts. I hope that the Government are thinking very hard about doing both those things. But while they are thinking, Parliament can act. We can start by granting a pardon to Turing, and we can continue by finding a way to amend the Protection of Freedoms Act to extend the disregard to all who were treated as cruelly as Turing was simply for being gay. We can start that process today with this Bill, and I beg to move. My new choral work, Codebreaker, has just been mentioned in the House of Lords by Lord Sharkey as part of his call to pardon Alan Turing. Watch the video below (wind on to 8mins 20secs for the actual reference). So as you've almost certainly realised by now, I've just launched my brand new website! I hope you like your new surroundings.

This is a very busy time as I'm currently drawing one big project to a close and embarking on the next one. Both are large oratorios/cantatas - still not sure what they are actually! - and will be premiered in London next year. The first is called Codebreaker is an hour-long work for choir, solo soprano and orchestra, that explores the life and tragic death of one of the 20th century's greatest minds: Alan Turing. This will be premiered by the Hertfordshire Chorus at the Barbican in April 2014. The second piece is a piece for choir, children's choirs and orchestra inspired by Malala Yousafzai, a girl who was shot in the head and neck by the Taliban in Pakistan for writing a blog for the BBC which supported girls' rights to an education. The libretto has been written by Bina Shah, a very brilliant Karachi-based novelist and blogger. This will be premiered by Crouch End Festival Chorus late next year. I'll try to be more diligent with my blog posting during the creative process of both of these works than I was on the old site - so I'll see you again soon! James 'Great art isn't about economics. It's about the ambiguity and restraint of Gerhard Ricter's September; the lyrical insight of James McCarthy's 17 Days, the breath-stopping horror of Jacobi's Lear, the exploration of personal landscapes of Akram Khan's Desh, the restless looking of David Hockney, or Lucien Freud. These works, these artists, some exalted, others setting out to develop their voices, tell us something about ourselves, about how we live and about what it is to be alive at this time.'(Liz Forgan, Arts Council Chair, State of the Arts speech, 2012) Read more at the Guardian

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed